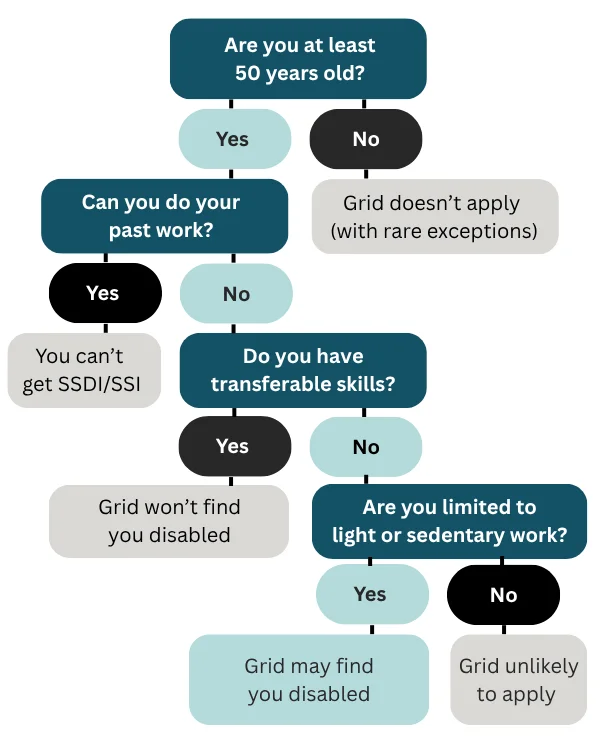

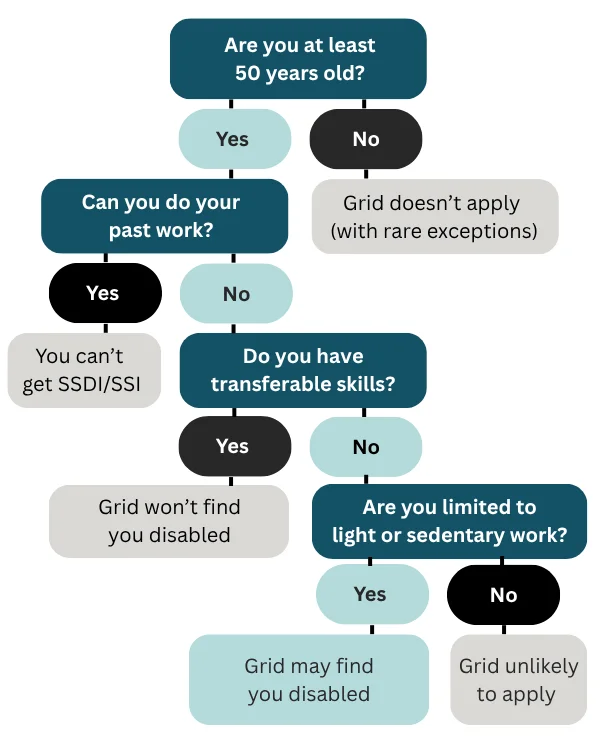

Learn the details about the medical-vocational grid rules and how they can help older claimants qualify for Social Security disability.

The Social Security Administration (SSA) recognizes that transitioning successfully to a new workplace or field becomes more difficult the older you get. For this reason, the agency has a set of guidelines called the "medical-vocational grid"—also called the "grid rules" or simply "the grid"—that makes it easier for claimants 50 years of age or older to qualify for disability. The grid is a set of factors that include your age, education, training, and exertional limitations.

The SSA uses the medical-vocational grid to determine whether you could be expected to switch to a new line of work before you hit retirement age. Claimants with certain "vocational profiles" can be found disabled using the grid even if they can perform other jobs. Because the grid makes it easier for you to get disability the older you are, if you're 50 or older, you should become familiar with the "grid rules" and how they can help you win your claim.

How Do the Medical-Vocational Guidelines Work?

Social Security doesn't expect people who are getting close to full retirement age (67, for most claimants) to switch careers or start over at the bottom of the career ladder. With that in mind, the agency created the grid rules as a way to find older claimants disabled even if they might be able to do some less physically demanding work. The grid takes the following factors into account:

- your age

- your education

- the skill level of your past work

- whether you could use any skills from your past work at another job, and

- your functional limitations.

If, due to a combination of the above, you're incapable of making a "vocational adjustment" to other work, the SSA must find you disabled according to the grid rules. (This is sometimes called a "directed finding of disability," because there isn't any discretionary leeway given to the disability adjudicator.) Below is a more in-depth look into how these factors are applied.

Grid Rules Factor #1: Your Age

Social Security classifies all disability applicants according to how old they are. The agency divides adult claimants into four age categories:

- younger individual (ages 18-49)

- closely approaching advanced age (ages 50-54)

- advanced age (ages 55-60), and

- closely approaching retirement age (ages 60-64).

The older you are, the more likely you are to be found disabled according to the grid. Most younger individuals won't be able to use the grid rules to qualify for benefits, unless they are very physically limited with an unskilled work history (or none at all) and can't read or write.

Grid Rules Factor #2: Your Education

Under the grid rules, Social Security divides educational levels into the following categories:

- illiterate (unable to read or write)

- marginal education (6th grade and below)

- limited education or less (7th through 11th grade)

- high school graduate or more (including GEDs), and

- recent, specialized training for a skilled job (such as nursing school).

Social Security refers to the last category as "education providing direct entry into skilled work." When applying the grid rules, this category doesn't come up often, but it can trip up claimants who have gotten training for a specific career within the past five years.

Keep in mind that claimants with postsecondary education (such as college or university) are treated as having a high school diploma for purposes of the grid rules.

Grid Rules Factor #3: Your Past Work Experience

The SSA classifies your past work according to skill level. Skill level is mostly determined by how long it takes to learn how to do the job and how complicated the job tasks are. Jobs are categorized as skilled, semi-skilled, or unskilled.

- Skilled jobs involve following complex instructions (such as a blueprint), working closely with others, and using abstract thinking. These jobs usually require at least one year of training or education. Examples include plumbers, administrative assistants, and real estate agents.

- Semi-skilled jobs involve detailed—but not complex—instructions. These jobs can be learned in a few months, and they tend to require manual dexterity and coordination. Examples include servers, cashiers, and security guards.

- Unskilled jobs involve simple, routine, and repetitive tasks. These jobs can be learned in one month or less. They can be easy, or very physically demanding. Examples include farm laborers, small parts assemblers, and laundry room attendants.

Grid Rules Factor #4: Transferability of Skills

If your past work experience was skilled or semi-skilled, the SSA will want to see if you can use any of those skills at a different job. Skills that you learned at one job that you can use in another are called transferable skills. Examples of transferable skills include:

- using basic software

- managing money

- keeping track of stock inventory, and

- filing and data entry.

Some skills are so tied to the physical nature of the job where you learned them that you can't use them to do a different type of work. Social Security considers these skills to be "not transferable." Depending on your residual functional capacity, not having transferable skills can be enough for the agency to find you disabled.

Grid Rules Factor #5: Your Residual Functional Capacity (RFC)

Your RFC is Social Security's determination of the most you can do, physically and mentally, in a work setting. The RFC assessment will frequently contain restrictions on how much weight you can lift and how long you can be on your feet for. The SSA refers to these restrictions as your "exertional level." The five exertional levels are defined below.

- Sedentary work. You can lift up to 10 pounds occasionally and 5 pounds frequently, and you can sit for 6 hours out of an 8-hour workday.

- Light work. You can lift up to 20 pounds occasionally and 10 pounds frequently, and you can stand and walk for 6 hours out of an 8-hour workday.

- Medium work. You can lift up to 50 pounds occasionally and 25 pounds frequently, and you can stand and walk for 6 hours out of an 8-hour workday.

- Heavy work. You can lift up to 100 pounds occasionally and 50 pounds frequently, and you can stand and walk for 6 hours out of an 8-hour workday.

- Very heavy work. You can lift more than 100 pounds occasionally and 50 pounds frequently, and you can stand and walk for 6 hours out of an 8-hour workday.

Most disability applicants are assigned sedentary, light, or medium RFCs. There is a different grid, with different rules, for each of these RFC levels. Your RFC might also contain non-exertional limitations you have that affect the types of jobs you can perform. Examples of non-exertional limitations include restrictions on how long you can use your hands to grasp objects, or whether you can interact with the general public. For more information, see our article on combining exertional and non-exertional limitations.

How You Can Apply the Grid Rules to See If the SSA Will Find You Disabled

To see how Social Security might decide your case, first find the table for your age group under the exertional level of your RFC. Next, find the row that describes your education level and previous work experience. The third column shows the decision the agency will make based on those two factors.

For example, if you're between the ages of 55-59 and have an RFC for sedentary work, below are the first few rows of the grid rules that could apply.

| Education | Previous Work Experience | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| Limited or less | Unskilled or none | Disabled |

| Limited or less | Skills that are not transferable | Disabled |

| Limited or less | Skills that are transferable | Not disabled |

If you have an 8th-grade ("limited") education and your past jobs were all unskilled, Social Security will find you disabled.

To see all of the grid rules, refer to our articles on the grid for your age group. If you're within six months of the next age group, you might want to read the article for that age group as well.

If Social Security thinks you have the residual functional capacity to perform the strenuous demands of heavy or very heavy work, you won't be able to use the grid rules to get disability benefits. You'll have to show that you have non-exertional limitations that prevent you from working jobs at any exertional level.

What If I'm Nearing the Next Age Group in the Grid?

If you're currently 49, 54, or 59 years old but are on the cusp of the next age group (for example, you're within a few months of your 50th birthday) Social Security might "bump you up" into the higher age category in certain circumstances. In these "borderline age scenarios," the SSA may evaluate your application under the relevant grid rules—even if you aren't technically old enough yet—provided you can demonstrate "additional vocational adversities."

What Are Borderline Age Scenarios?

Social Security's rules outline a two-part test for figuring out when a disability claimant's application could constitute a borderline age situation. If the answer to both of the following questions is yes, then the agency may apply the next highest grid rule provided the applicant has additional vocational adversities.

- Is the claimant within a few days or months of the next age bracket? It's not clear from agency policy how many months constitute "a few," but in practice it's rarely more than six. For instance, someone who is 54 years and 10 months would qualify as being close to the 55-59 age bracket.

- Would using the claimant's real age result in a finding of "not disabled," and would using the higher age category result in a finding of "disabled"? If changing the age category would make a material difference in the outcome of the application, the SSA will then consider using the higher age category for purposes of determining disability. If changing the age category wouldn't alter the result—for example, there isn't enough evidence to establish a severe impairment—the agency will use the claimant's actual age.

Being close to the next age category doesn't automatically bump you up, however. The SSA still needs to consider whether you have additional vocational adversities that warrant application of a more favorable grid rule.

What Constitutes an Additional Vocational Adversity?

"Additional vocational adversities" are special considerations related to a claimant's education, RFC, or work experience that suggest to Social Security that it would realistically make more sense to use a higher age category than it would to use a lower one. Generally, they refer to aspects of the claimant's life that aren't fully contemplated by the grid rules. Additional vocational adversities may come in the following forms:

- Very limited education. Under the grid rules, a 55-year old who didn't graduate high school, only worked at unskilled jobs, and is limited to light work is considered disabled, while a 54-year old with the same vocational profile isn't disabled. But if the 54-year old is several weeks out of their 55th birthday and not only didn't graduate high school but wasn't educated past the 6th grade, their limited education can count as an additional vocational adversity.

- Nonexertional limitations in your RFC. The grid rules are based on strength-related ("exertional") limitations on how much weight you can lift and how long you can sit, stand, and walk. But nonexertional limitations, such as trouble bending, loss of vision, or difficulty focusing on tasks, can also interfere with your ability to work. Whether you're right- or left-handed can even come into play, since the number of jobs you can do is decreased when you can't use your dominant hand for tasks such as typing, pinching, or driving a manual transmission.

- Work experience in an isolated industry. If your past jobs were in "isolated" or highly regional industries, such as fishing or logging, Social Security may count this as an additional vocational adversity. Claimants with work in isolated industries are often evaluated as if they have no job history, not even for unskilled work. Having no job history is considered an additional vocational adversity, since it puts claimants in a worse position than if they had unskilled work. So if the next highest age group directs a finding of disability when a claimant has "no past work," the agency can place you in the higher category for purposes of applying the relevant grid rule.

Keep in mind that Social Security claims examiners and disability judges aren't under any obligations to use the borderline age rules, and have wide discretion to determine whether additional vocational adversities exist. But if you've held unusual jobs in the past or have unique skills, you may successfully convince the agency to apply a more favorable grid rule based on a borderline age scenario.

Ways to Win Disability Outside of the Grid Rules

Even if the grid rules don't call for a finding of disability, you can still qualify for benefits if you can show that no jobs exist that you can do despite your limitations. (This is the most common way that the SSA awards benefits to people under the age of 50.) Here are several ways for you to show the agency that you can't do any jobs:

- You physically can't perform even sedentary work. Sit-down jobs require you to be able to lift 10 pounds and be on your feet for 2 hours in an 8-hour workday. If you can't lift more than 5 pounds, or can only stand and walk for 1 hour total, the SSA will find you disabled.

- You have non-exertional limitations that eliminate all work. If you can only use your hands for half of the day due to carpal tunnel syndrome, or you need to elevate your legs every 15 minutes to relieve back pain, the agency will likely find that no jobs exist in significant numbers that you can perform.

- You're unable to meet the demands of competitive employment. Taking too much time off or being unable to concentrate on your job tasks due to your medical condition can mean that the SSA doesn't think any employer would hire you for full-time work.

Whatever your health conditions may be, make sure that you have the medical evidence you need to back up your limitations. Social Security can't award benefits based on symptoms alone—you'll need to establish that you have a medically determinable impairment as documented by an acceptable medical source.

Getting Help With Your Disability Claim

The grid rules can frequently help older people win their disability claims, but understanding the nuances of how Social Security uses the grid can be confusing. An experienced disability representative can help determine where you fall within the grid and what your options are. Most disability lawyers work on contingency—meaning they only get paid unless (and until) you win—and many offer free consultations, so there's little risk in asking around to find an attorney who will be a good fit for your claim.