Here's a basic introduction to how Social Security disability works, what it takes to qualify for SSDI benefits, and how you can apply.

Social Security Disability Insurance, or “SSDI,” is a federally administered cash benefits program that provides monthly payments to people who become disabled before reaching retirement age. (Because SSDI eligibility is based in large part on your employment and earnings history, it’s sometimes known as “workers’ disability.”) You may qualify for SSDI if you have a medical impairment that keeps you from working full-time for at least twelve months.

While many people use the terms SSDI and SSI (for Supplemental Security Income) interchangeably, there are significant differences between the two programs—namely, the non-medical requirements that determine which benefit you’re legally allowed to receive. If you’re considering applying for disability benefits but aren’t sure which program is right for you, read on to learn about the medical and financial criteria needed to qualify for SSDI.

- What Is Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)?

- Non-Medical Eligibility Requirements for Social Security Disability

- How Social Security Decides If You Have a Qualifying Disability

- How Much Are SSDI Benefits?

- How to Apply for SSDI Benefits

- What Happens If I’m Approved For SSDI?

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About SSDI

- Do You Need to Hire a Disability Lawyer to Get SSDI Benefits?

What Is Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)?

As the name suggests, SSDI is an insurance program—funded by payroll taxes (FICA) or self-employment taxes (SECA)—that offers benefits to disabled adults who can no longer work. When you work and pay taxes into the Social Security Trust Funds, you gain insurance coverage that can help support you if you become disabled and need to draw benefits.

SSDI benefits are only available to applicants Social Security considers permanently disabled, meaning they’re totally unable to work full-time for one year or more. People who are partially or temporarily disabled won’t qualify for SSDI. Instead, they’ll have to rely on other financial resources—such as private short-term disability insurance, workers’ compensation, or paid medical leave, if offered in their state—to help get them through periods where they can’t work for health reasons.

Non-Medical Eligibility Requirements for Social Security Disability

Before Social Security can determine whether your medical condition is disabling, the agency first needs to see if you satisfy the preliminary legal criteria for the SSDI program. In order to be able to receive SSDI benefits, you must have earned enough “work credits” to become insured for benefits as of your disability onset date.

Work credits are determined by the amount of wages you earn in a year. In 2026, you gain one work credit for every $1,890 you make each year. (Only earnings you paid Social Security taxes on count toward the total.) You can gain up to four work credits per year. The exact number of work credits you need to establish eligibility for SSDI depends on how old you were when you became disabled.

For example, let’s say you were 50 years old when you became disabled. In that case, you’d need 28 work credits—or seven years of work—to qualify for SSDI benefits, and you must have worked at least five of those years within the last 10 years. (You can learn more in our article about the legal and financial requirements for SSDI.) If you haven't worked long enough (or worked at all) when you become disabled and you have limited resources, you may be able to apply for SSI instead.

How Social Security Decides If You Have a Qualifying Disability

Once Social Security has determined that you have enough work credits, the agency will then check to see if you qualify medically for disability benefits. That means you must have one or more severe impairments that keep you from working at the level of substantial gainful activity (SGA) for at least one year. In 2026, the SGA amount is $1,690 per month, or $2,830 if you’re blind.

You might be able to get benefits even if you’re still working, but not if you’re earning more than the SGA limit. As long as you aren’t earning at or above the SGA amount, you can satisfy Social Security’s definition of disability in one of two ways—by meeting the requirements of a “listed impairment” or by showing that your “residual functional capacity” prevents you from doing any kind of full-time work.

Meeting a Listed Impairment

Social Security’s Blue Book is a catalog of medical conditions that the agency considers particularly serious. Each condition in the Blue Book is called a listed impairment, and each “listing” lays out a set of medical criteria that, if documented in your records, can qualify you for disability without having to show that you can’t work at all.

Under Social Security’s sequential evaluation process, the agency will first check your medical records to see if your condition meets (or equals) the requirements of a listing. If it does, you'll be considered disabled and get approved for benefits. If not, you might still qualify for SSDI if no jobs exist that you can do despite your medical impairments.

Getting Approved Because You Can’t Do Any Job

Social Security will look at your medical records and activities of daily living to determine what you’re still capable of doing despite your impairments—a process called assessing your residual functional capacity (RFC). Your RFC is a description of your maximum physical and mental capabilities and contains work-related limitations that restrict the types of jobs you can safely perform.

The agency compares the limitations in your RFC against the duties of your past jobs to see whether you could still perform them today. If not, then Social Security will determine if you can do any other kind of work, using a combination of factors including your RFC, age, education, and skill set. If no other jobs exist in the national economy that you perform on a regular basis, you’ll be awarded benefits in what’s called a medical-vocational allowance.

How Much Are SSDI Benefits?

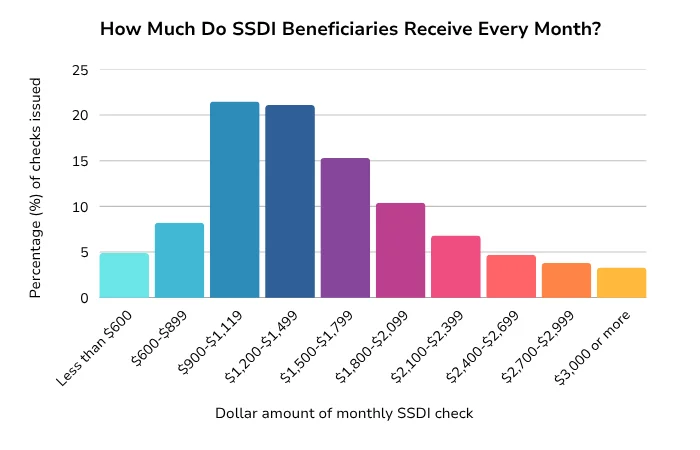

If you’re awarded SSDI, the exact amount you’ll get is calculated based on your past earnings. Your SSDI monthly benefit amount can range from $100 to $4,152 (in 2026). Most SSDI recipients receive between $800 and $1,800 per month, with the average individual disability benefit at $1,630 per month. In addition to monthly cash benefits, you can get healthcare benefits through Medicare (after two years). SSDI benefits might also be available for your spouse and other dependents.

Source: Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2023

While SSDI (unlike SSI) isn’t an income-based program, the amount of your disability benefit can be reduced if you’re also collecting workers’ compensation or temporary state disability. But receiving private disability insurance payments, veterans benefits, or SSI won’t reduce your SSDI benefit amount.

How to Apply for SSDI Benefits

Filing for Social Security benefits is a fairly straightforward process. There are multiple ways you can submit your claim:

- Use the application tool provided on Social Security’s secure website. Before you start, you may first want to read our article with tips for applying online.

- Call Social Security’s national number at 800-772-1213 from 8:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., Monday through Friday, to speak with a representative. If you’re deaf or hard of hearing, you can use the TTY number at 800-325-0778.

- File in person at your local Social Security field office. Offices are typically open weekdays from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., but you may need to make an appointment.

No matter which method you choose, it'll help if you have some information already gathered when you start. Social Security will need:

- your name, address, and Social Security number (SSN)

- if you're married, your spouse's name, address, and SSN

- your work history, including dates of employment, employers' names, your job title, and the type of work you performed

- medical information for all the doctors you've seen for MS and any hospitals you've been admitted to.

For more comprehensive details, including what personal information you should have on hand when you apply, check out our article on filing a disability claim with Social Security.

When Should I Apply for SSDI?

As soon as it becomes clear to you that you will be unable to work for at least twelve months due to a medical condition. The earlier you can establish your protective filing date, the more likely you’ll be able to receive SSDI backpay—a necessity given how long it takes, on average, to get approved for benefits. You can find more information in our dedicated article on when you should file for disability benefits.

What Happens If My SSDI Claim Is Denied?

If your application for SSDI is denied—as most initial applications are—you have 60 days from the date you receive the denial letter to appeal the decision. The first level of appeal is the "request for reconsideration," where a different disability claims examiner reviews your file. If you’re denied again, you can appeal further by asking for a hearing with an administrative law judge. Disability hearings are where most winning SSDI claims are approved. (Learn more about Social Security denials and the appeals process.)

What Happens If I’m Approved For SSDI?

After you’re approved for SSDI, Social Security will mail you an award letter detailing how much you’ll get in monthly benefits, describing what backpay you’re entitled to, and outlining the payment schedule for your monthly checks. (Keep in mind that the SSDI program has a five-month waiting period during which you won’t receive payment.) Past-due benefits are paid in one lump-sum amount, but ongoing SSDI payments are made on a monthly basis.

You can keep receiving SSDI as long as your medical condition prevents you from working. Social Security will perform a continuing disability review of your file every few years to determine if your condition has improved enough for you to return to work. (Learn how you can try going back to work without risking your SSDI benefits.)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About SSDI

Below are answers to some other frequently asked questions disability claimants have about SSDI.

How Long Does It Take to Get SSDI?

Broadly speaking, you should expect to wait around two years from the date you file your SSDI application and the date you begin to receive benefits if you’re approved (although some people get a much quicker disability determination). The breakdown typically goes like this: six to eight months for the initial determination, five months for reconsideration review, seven to twelve months for a hearing, and one to two months after the hearing to receive the judge’s decision.

Are SSDI Benefits Taxable?

They can be. If your household income is over a certain amount, you may have to pay federal taxes on your disability benefits. Most states don’t levy state income tax on SSDI, but about a dozen states do tax Social Security benefits.

Can You Work While On SSDI and If So, How Much Can You Make?

Yes, you can work on SSDI—up to a point. The Social Security Administration has several programs (such as Ticket to Work) intended to help disabled people hold down jobs without worrying about risking their benefits if they’re not successful. However, if you start consistently making more than the SGA amount and you exhaust both your trial work period and extended period of eligibility, your disability benefits may stop.

How Can I Check My SSDI Application Status?

You can check your application status online or over the phone. In order to check your status online, you’ll need to set up an account with login.gov. Or, you can use Social Security’s 24/7 automated phone assistance system at 800-772-1213.

Do You Need to Hire a Disability Lawyer to Get SSDI Benefits?

No, it’s not required, but it’s generally a smart idea. Having an experienced disability attorney on your side can greatly increase your chances of winning your claim, especially if you’ve already been denied once and need to submit an appeal. The following articles can give you an idea of what’s involved when deciding whether to get an attorney:

- Should You Get Legal Help For Your Disability Claim?

- What Do Social Security Disability Lawyers Do?

- Is a Disability Lawyer Worth It?

- Should I Hire a Disability Lawyer or Nonattorney Advocate?

If you’re worried about the cost of legal representation—as many claimants are—it’s important to know that disability attorneys work on contingency, meaning they don’t get paid unless (and until) you win your claim. Many offer free consultations or work pro bono for legal aid offices, so there’s little risk in asking around until you find a lawyer who’s a good fit.

- What Is Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)?

- Non-Medical Eligibility Requirements for Social Security Disability

- How Social Security Decides If You Have a Qualifying Disability

- How Much Are SSDI Benefits?

- How to Apply for SSDI Benefits

- What Happens If I’m Approved For SSDI?

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About SSDI

- Do You Need to Hire a Disability Lawyer to Get SSDI Benefits?